|

Music Studio |

|

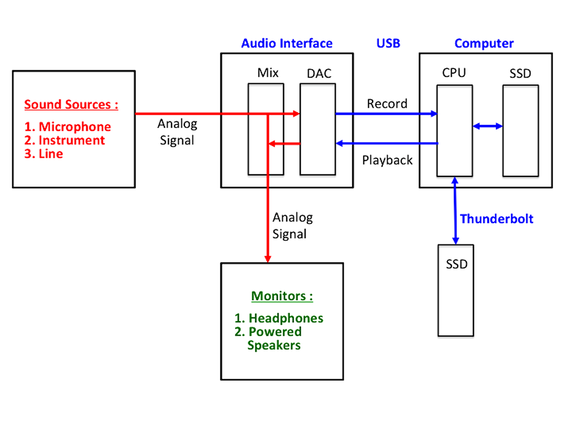

Latency refers to the buildup of time delays, measured in milliseconds (ms), in digital audio signals as they pass through the hardware/software of the computer-based recording system. Looking at the digital signal flow in the block diagram above, we can see delays can be caused by the following processes:

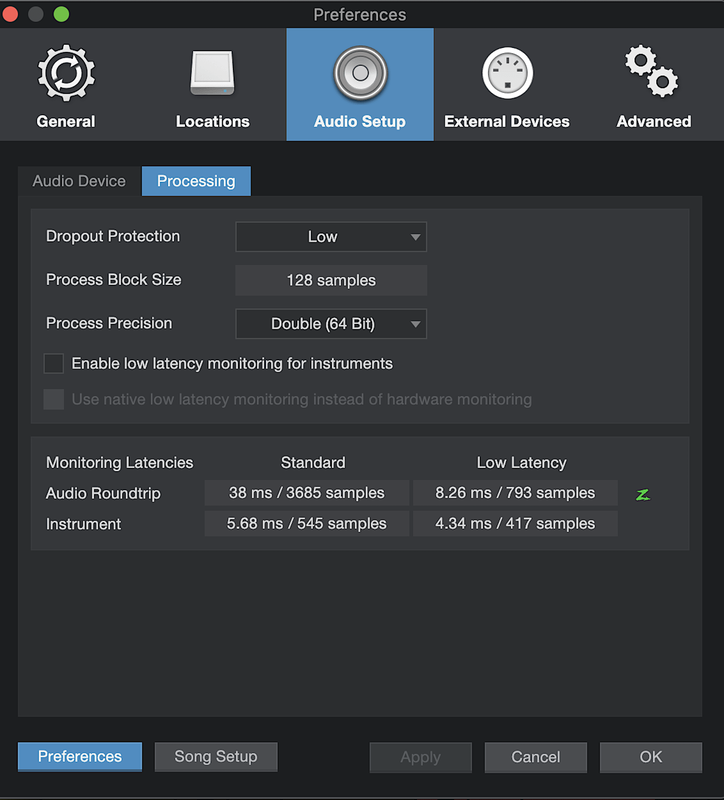

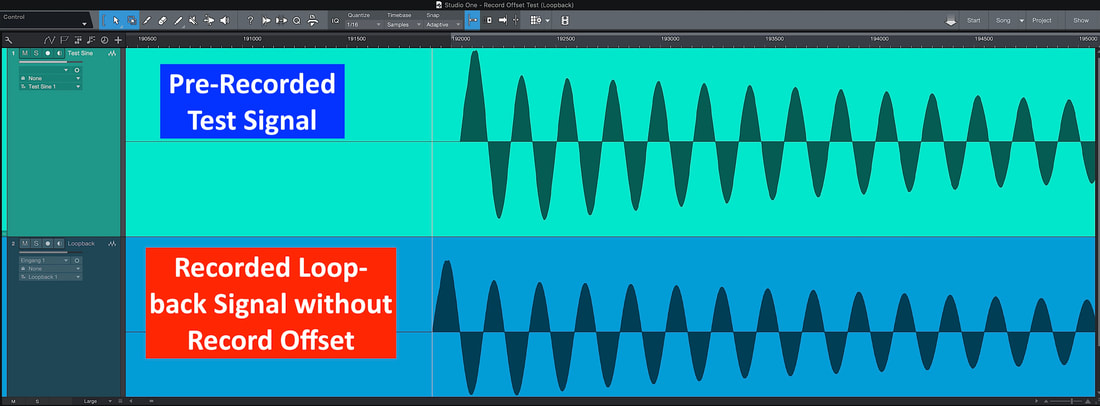

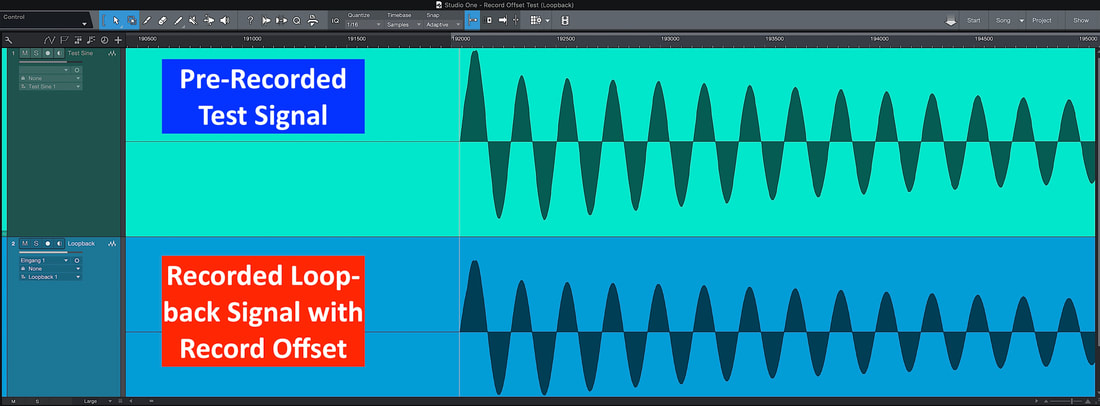

There are two activities associated with recording where latency can be a significant issue – monitoring and overdubbing. Monitoring When recording, you want to hear your performance as you play, as well as the performances of others if you’re playing with a group. This is called monitoring. When monitoring the music being played through your computer’s signal path, latency can be experienced as short delays between the time you play a note and the time you hear it on your headphones. If this delay is excessive, say, more than 8 – 10 ms, then it will be nearly impossible for you to play well on your own instrument, not to mention playing with a group. The largest contributors to latency are numbers 2 and 3 in the list above. The availability of audio interfaces using Thunderbolt-3 (40 Gbps) connection to the computer has dramatically reduced latency. For computations made in the CPU for signal processing, there is a need for buffering data. By setting the buffer block size to a minimal amount ( 64 or 128 samples) in your DAW, we can reduce latency. A process block size of 128 samples is shown below for the PreSonus Studio One DAW. Using a small buffer block size is possible only if your CPU has the ‘horsepower’ to make the necessary computations quickly enough. Otherwise, data “drop outs” and system instability can often result. In the case where you must user larger buffer block sizes to have a stable system (causing unacceptable latency), most DAW software comes with a “low-latency” option for the monitoring signal path. In essence, the computer returns a portion of the digital audio data immediately back to the audio interface for monitoring purposes, without performing any significant signal processing. In the Studio One DAW example above, the round-trip audio monitoring latency is an unacceptable 38 ms. With the low-latency option engaged, the round-trip monitoring latency is reduced to a useable 8 ms. In keeping with the ‘philosophy’ of returning the monitor signal back to the performer as soon as possible, why not use the analog signal before even digitizing it ?! Makes sense. And I believe this is what is routinely done in practice by many people, including me. Most quality audio interfaces have signal routing and monitoring mix capabilities -- this is shown by the red color arrows in the signal path block diagram at the top of this post. In this approach, called “hardware monitoring” , there is literally zero latency. You hear what you and your group are playing immediately in your headphones. Great ! Overdubbing Overdubbing is the practice of listening to the playback of previously recorded tracks and recording an additional, separate track to the computer audio file that is “in synch” with the previously recorded tracks. The key word here is “in synch” -- timing is everything. Envision the signal flow using the block diagram at the top of this post. The playback signal originates from the audio file on an external SSD drive and travels all the way to the monitor output on the audio interface. Upon hearing this signal, you play right along with it, hopefully “in synch” . Your new signal at the audio interface input now travels all the way back to the external SSD drive and is recorded on a new track in the audio file. You can imagine that the round-trip latency will “place” the new track data somewhat delayed on the time line from the original playback track – i.e., NOT in synch ! So, upon close inspection of the audio waveforms displayed by the DAW, I would expect the timing of the new track waveform to lag behind the original track waveforms. What I see, however, when I do this is that the new track waveform actually PRECEDES the original track waveform on the time line by some number of samples !! So my DAW is doing something that is not readily apparent, like trying to guess where to place the new track waveform properly on the time line. Only the software developers know for sure what is going on here. Fortunately, there exists a very short tutorial video from the PreSonus folks on performing a “loop back” test to ascertain how to align the two waveforms properly on the time line. A previously recorded transient on one track is played back to the monitor output of the audio interface and is then routed, via an audio cable, right back into the input of the audio interface to be recorded on a second track -- hence the name “loop back” test. Ideally, latency would be insignificant, and the two transient waveforms would be nearly aligned on the time line, i.e., they would almost be “in synch” . But this screen shot shows the result : The timing of the newly recorded transient PRECEDES the original transient by approximately 132 samples. By going deep inside the menus on the DAW, one can find, under the advanced audio settings, an input box labeled “Record Offset”. Here, you enter the 132 sample number. Rerun the loop back test. Lo and Behold -- the two transient waveforms line up nearly perfectly !! Amazing. I am left wondering why such an important topic of aligning overdubbed tracks in the recording process is left to a relatively obscure tutorial and a menu item that is so deeply buried. It may be that the small offset is not readily detected aurally by a casual listener. But I am of the opinion that precision here is very important. Note: The Record Offset value obtained from the loop back test is completely dependent on the settings for your recording -- sample rate, bit depth, computation precision, and buffer block size. Also, there are no FX plug-ins inserted in the playback channels. So if you change any of these, a loop back test would need to be run again to get the correct value for the Record Offset. OK, in the next post, we’ll take a look at the signal path in the digital audio workstation software for recording and mixing.

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed