|

Music Studio |

|

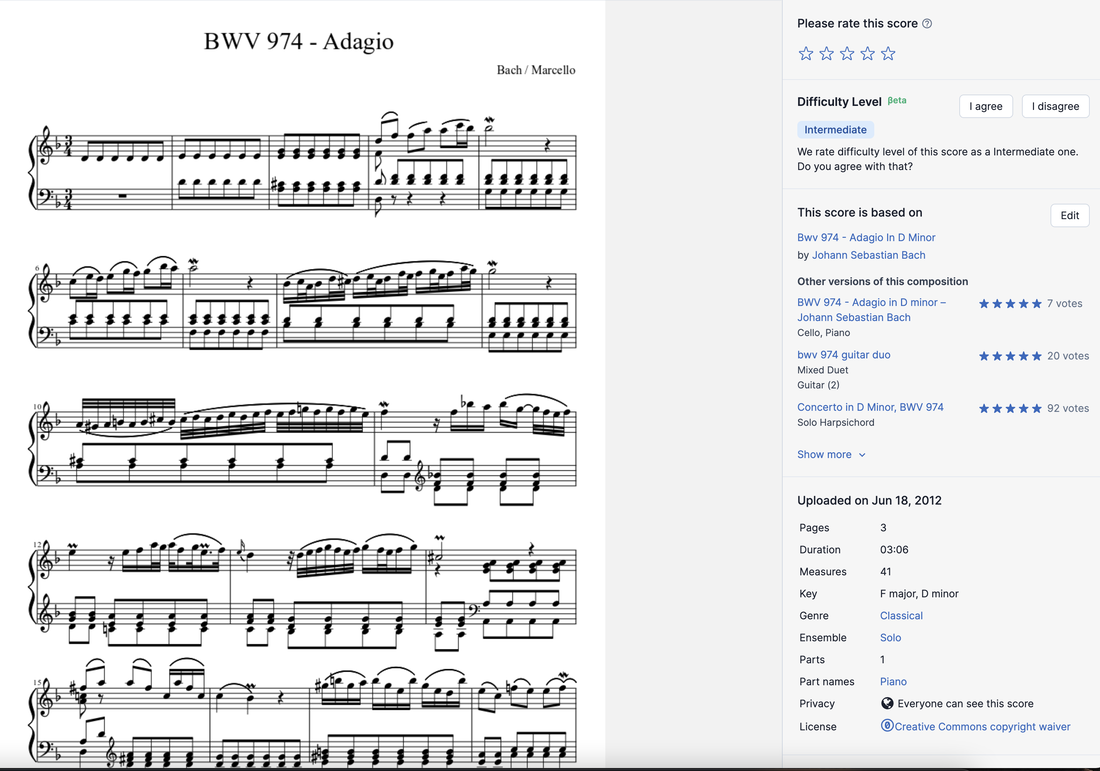

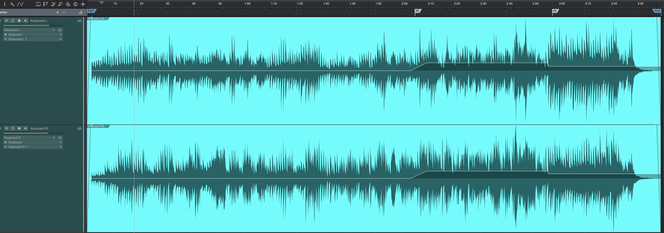

In the next four posts, I’ll provide an overview of the four steps for creating a musical recording that will be posted on a streaming platform. The four steps are recording, mixing, mastering, and streaming. In this first post, I’ll cover the recording of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Adagio in D minor for solo keyboard. This piece is very popular, and has been used in the soundtracks of several films, including Coda (2020) and Fifty Shades of Grey (2015) . This Baroque-era work is emotional, meditative, even a bit dark, with a beautiful upper melodic line undergoing many stylistic ornamentations over a slowly plodding, steady progression of chords in the low-mid register. The Adagio is a solo keyboard arrangement of the second movement of Bach’s Concerto in D minor, BWV 974, which in turn is a transcription of the Concerto for Oboe and Strings in D minor composed by Alessandro Marcello. Bach’s autograph of this keyboard arrangement has been lost, but the arrangement was copied around 1715 by Bach’s second cousin, Johann Bernhard. It is this copy that we use today to perform the Adagio. To perform this work, I obtained a public domain (Creative Commons license CC0) score of the music from Musescore. Technically, this is not a difficult piece to play. But the artistry is in the articulation and expression of the ornamental melodic line, and in the nuanced tempo variations. This is why a ‘live’ performance of this work is so important. A MIDI-programmed virtual-instrument grand piano cannot fully capture the needed artistry, even with its articulation control, velocity profiles, and quantization and timing editing. I recorded the piece in five ‘takes’ and used an editing process called “comping” , short for “compositing”, to splice together the four best sections from the takes. Two sections are joined together using a painstaking process of aligning sound waveforms from both sections and applying amplitude cross-fading. If done properly, there will be a smooth transition in timing and dynamics between the two sections, with no audible clicks ! This splicing has to be successful musically as well as acoustically. Since the left and right piano tracks are the only ones playing, an imperfect splice cannot be masked by the sounds of other instrument tracks playing. Lastly, the gain (loudness) profile of the recorded waveforms in both left and right channels is slightly edited to achieve the desired dynamic character in the overall recording. I prefer to use nondestructive "clip gain" editing of the recorded waveforms, rather than volume automation of the channel faders during the mixing process. The final recorded sound waveforms are shown below in the PreSonus Studio One Pro digital audio workstation. In a previous post, long ago, I talked a bit about the philosophy of editing recorded waveforms. I want to repost some of those comments here, as I think it is worth being reminded of the ‘goal’ of editing. When the recording “red light” comes on, it’s only natural to feel ‘nervous’ , just like you would feel performing the music in front of a live audience. You’re thinking: “This is it. What I record into the digital audio file is permanent. I’ve got to “get it” just the way I want, so that listeners will hear and enjoy a good musical performance.” This is why it is necessary to have done all the hard work of practicing the piece to a sufficient level of technical mastery beforehand. And then, take a lot of time to allow your playing to develop and mature the musical ideas you wish to convey. Now, you can concentrate on the interpretation and musicality of the piece while recording the performance. It is unreasonable, however, to expect to be able to “lay down” your very best performance in a single complete “take” . It is very comforting to know that you can, and will, use some editing of the recording, during the recording session as well as afterwards, to put together a performance you are happy with. Here are some excellent thoughts about the philosophy of editing expressed by the pianist Paul Cantrell on his website: "An aside on the philosophy of splicing: I'm skeptical of classical recordings with hundreds of splices that are pieced together entirely in the studio — it works well when the studio is part of the compositional process, but when the purpose of such splicing is obsessively perfectionist correction of live playing, it is dangerous. It can lead to a clinically perfect but spiritless recording without the organic expressiveness that makes music magical. However, neither am I in the camp that decries splicing as some kind of hoodwink or moral failing; recordings are recordings, not live performances, and a musician's job is to work their medium's full potential to produce the best possible experience. So, when I splice, I try to strike a balance between correcting really conspicuous mistakes that disturb the flow of the music, and preserving that flow in its natural form. In short: splices are artistic decisions, and must be treated as an aspect of musical performance, not as cosmetic surgery. End of aside." In the next post, I’ll talk about the mixing step in the creation of the musical recording of Bach’s Adagio in D minor for keyboard solo.

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed